BACK TO RESEARCH WITH IMPACT: FNR HIGHLIGHTS

For each Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting, the FNR runs a Call for promising young researchers with a connection to Luxembourg to attend. The 2024 Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting was dedicated to physics. We spoke to Research Fellow Foni Raphaël Lebrun-Gallagher about the experience.

You had the opportunity to hear from and meet Nobel Prize winners and hundreds of other young researchers, can you describe the overall experience?

“Absolutely unforgettable! As the date drew nearer, I was becoming increasingly more excited about the event. Reading about the past experiences of some of the young researchers that had already attended the conference, my expectations were high! A week before the conference however, I started to have a slight worry in the back of my mind: maybe the atmosphere would not be quite as I was imagining it. It was of course easy to imagine that there will be many passionate debates and discussions. But academic-only exchanges can easily trump more humanist and holistic ones. After all, typical selection processes based on academic achievements alone tend to reward those who are highly self-confident and objective focused.

“To succeed as a researcher, people may then, favour ends over means and put themselves first at the expense of others. While not common, it is then not rare to attend conferences that suffer from this behaviour. On these occasions, the atmosphere can easily turn clannish, and the broader picture can easily be set to side.”

“On the first day of the conference, all my initial worries were quickly put to rest. The inspiring opening ceremony, which in part recounted the life of Albert Schweitzer and his dedication to humanitarian work, clearly set the tone. The conference had overall a wonderfully relaxed atmosphere.

“Nobel laureates were of course celebrated, but it was also clear that they were eager to meet and exchange with the next generation of young researchers. But most of all, the event was a celebration of science, scientists, and the human qualities that it calls onto them to embody: the curiosity to look where no one looked before; the courage required to overcome setbacks and repeated failures; as well as a drive for innovation to push society forward as a whole and equipe it with the tools that it needs to face its most pressing challenges. But to do research effectively, one key ingredient cannot be left aside: collaboration.”

“Science is at its core a collaborative endeavour. It requires an open mind, to discuss beyond disagreements, to investigate your own biases, and to promote a diversity of thoughts. With over 50 Nobel laureates and rooms filled with top young scientists coming from over 90 countries the energy and enthusiasm was phenomenal. Lindau, to me, felt like an event which was deeply committed to being outward looking. It could not have embodied its moto “Educate. Inspire. Connect” any better. It reminded us of all, in the liveliest way, of the reasons that led us to do science in the first place. ”Foni Raphaël Lebrun-Gallagher Research Fellow in Trapped Ion Quantum Computing at the Sussex Centre for Quantum Technology (SCQT) at the University of Sussex

What was your impression of the Nobel Prize Winners?

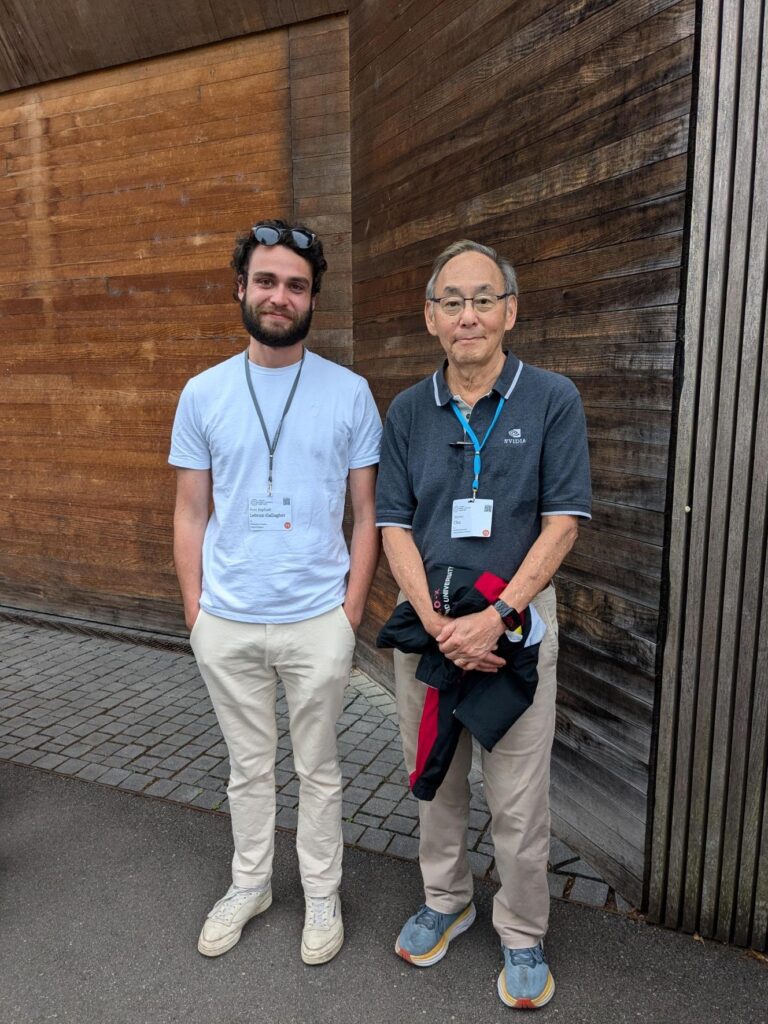

“The times when you meet a Nobel laureates in your career come far and few. So, a time where you see and hear from around 50 Nobel Laureate in a single week feels completely surreal. Since everyone is eager to engage with them, small, yet daunting, audiences can quickly gather around them. But a week is long enough and filled with so many opportunities that everyone is given a chance to engage with them.

“I was amazed by how keen they were to talk to and with young scientists. To share their experiences as researchers: the obstacles they encountered, the fights they had to pick and how success came around, but also how keen they were to learn from the difficulties that this generation of scientists is going through. What they would do in our place, their perspective on the subjects, and how they can help shape research environments so that it benefits scientists and science as a whole in the long term.”

What were your highlights of the scientific programme?

“Being a quantum physicist, I was looking forward to the lecture talk from Alain Aspect entitled “from Einstein and Bell to quantum technologies: quantum non-linearity in action”. Being able to listen to the history of the development of quantum technology from its origins to present day being recounted by one of its most prominent actors was a unique experience.”

“I was also particularly interested in the talk from Eric Betzig discussing the opportunities and challenges for the energy transition. A subject outside of my research field, but one I feel strongly involved with. I believe it was a key talk at the conference. It provided a strong reality check with regards to where society is at on this monumentally pressing challenge and conveyed rightly the sense of urgency with regards to the actions society needs to take. While most of the audience was already acutely aware and engaged on the subject in one way or another, the talk acted as both the spark and catalyst for discussions between young researchers that lasted to rest of the week.”

Were there any current topics that came up from several Laureates or researchers in attendance?

“Surprisingly, or perhaps unsurprisingly, the topics that were the most recurrent in conversations were topics that are also, I believe, on most people’s minds: the increasing polarisation of our world and climate issues.”

“With tensions rising between powers across the globe, the resurgence of war in Europe, the increasing likelihood of voluntary or involuntary nuclear conflict, the erosion of the internal political discourse together with the deterioration of compassionate dialogue between political groups within western democracies, there seems to be a growing threat to society in the short term. Climate issues and increasing our effort towards mitigating carbon emissions also pose immense challenges that require actions to be taken today and to continue sustainably. Achieving one of these goals is difficult enough, achieving both may seem almost unsurmountable.

“And so, many conversations revolved around how, as scientists, we can contribute towards these goals. What action can we take at our level? What role can quantum technologies play in this area? What impact may AI have in this context? And, more broadly, what role must scientists play as part of active members of society?”

“I think we found ourselves to be all in agreement that science and knowledge must be disseminated, that it is an international endeavour and the role of science diplomacy cannot be understated. When communication breaks downs and everyone stops talking, scientists have a responsibility to talk to, and with, the society the live in to share their expertise. They also have a responsibility to keep communication channels open across countries in spite of disagreements and divides. We have all an inherent responsibility to making science open and accessible, because knowledge is universal, and its pursuit cannot be done alone. And so, when no-one is willing to work together any longer, scientists must. ”Foni Raphaël Lebrun-Gallagher Research Fellow in Trapped Ion Quantum Computing at the Sussex Centre for Quantum Technology (SCQT) at the University of Sussex

Did you find any inspiration at the meeting, for your work or outside?

“Without doubt! The meeting was by nature incredibly scientifically diverse with physicists working on fields that were extremely remote from each other’s. It was really refreshing to see the angle of approach that some researchers followed to tackle their problems and how it could inspire novel approaches to the problems that I am facing in the lab.”

“But what has marked me most is this feeling of hope that I have rarely found myself experiencing so intensely. In the lab, it is easy to keep your nose to the grindstone.

“Scientific research is, in its essence, an iterative repetitive process of trial and error. And it is easy to get stuck in the technicalities and lose touch with the overall field or feel detached from the emerging challenges that are only tangentially related to your work. At the conference, I felt deeply inspired to be in a place where we celebrated the fundamental values of scientific research that I talked about before. The event was filled with raw curiosity fuelled by the hope and the prospect of improving people’s lives. Physicists from all backgrounds were willing to talk and work together. Each was bringing with them their unique expertise to the table so that action could start here and now to tackle some of the hardest challenges. None of them felt too big.”

Can you tell us a bit about your research, what do you study and why is it important?

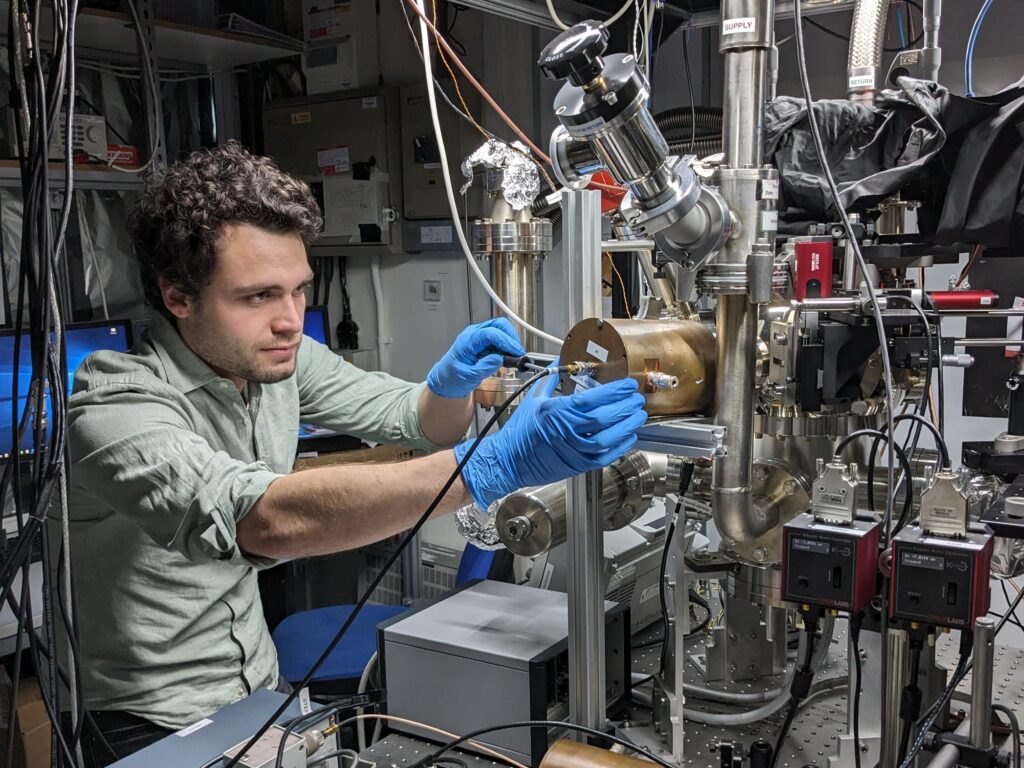

“My research field in trapped ion quantum computing. That is the field of physics where we aim to manipulate individually trapped charge atoms with increasingly more precision. At this scale, the properties of individual atoms and their dynamics can only be described quantum mechanically. In the lab, we can interact with the electronic structure of single atoms to encode quantum information within it such that it can be used as the building block of a quantum computer. Such a building block is commonly referred to as “quantum bit” or “qubit” in short.”

“Quantum computers have long been regarded as being a ‘holy grail’ of science as they have the potential of significantly impacting people’s life. As opposed to a classical computer, a quantum computer uses the rules of quantum mechanics to perform computation. By effectively utilising this new (and different!) set of rules in the computer’s hardware, specific computational problems that would be otherwise intractable even with today’s most powerful classical supercomputers could become within reach. This technology is currently expected to play a key role in solving some of the most pressing global issues, with quantum computers being set to find applications to the development of medicines, creating new highly advanced materials, assisting with food security, as well as potentially unlocking solutions to the climate crisis. “

“While quantum computers already exist today, they remain constrained by the number of qubits available to them and the precision with which quantum operations can be executed. To be able to unlock the computational power required to solve high-impact problems of practical significance, quantum computer hardware must be engineered to allow for qubit numbers to scale up while simultaneously avoiding any compromise on the reliability with which quantum information is manipulated.”

“At the University of Sussex, my work focuses specifically on investigating a novel approach to interconnecting quantum processing modules such that the number of qubits afforded within a single computer will be capable of reaching the qubit numbers required for practical use. The approach consists of transporting individually trapped ion qubits between quantum processing units and paves the way towards fast connection speeds without loss of quantum information. ”Foni Raphaël Lebrun-Gallagher Research Fellow in Trapped Ion Quantum Computing at the Sussex Centre for Quantum Technology (SCQT) at the University of Sussex

Related highlights

“Truly epic—a once-in-a-lifetime event”

For each Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting, the FNR runs a Call for promising young researchers with a connection to Luxembourg…

Read more

“Incredible to witness their joy and passion for science”

For each Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting, the FNR runs a Call for promising young researchers with a connection to Luxembourg…

Read more

2023 Lindau Meeting: “An extraordinary experience”

For each Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting, the FNR runs a Call for promising young researchers with a connection to Luxembourg…

Read more

“Like a school summer camp, but with amazing young chemists and Nobel laureates”

For each Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting, the FNR runs a Call for promising young researchers with a connection to Luxembourg…

Read more

“Hearing how different life decisions and habits can lead to very successful scientific careers”

For each Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting, the FNR runs a Call for promising young researchers with a connection to Luxembourg…

Read more

“They are normal human beings like you and me”

For each Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting, the FNR runs a Call for promising young researchers with a connection to Luxembourg…

Read more